Common Core aligned books and the drill to teach reading to young children, appears to ignore the real questions children might have about the stories they read. This could be serious, especially if the book is beyond a child’s development. If the teacher is forced to address things like syntax, story order, and facts surrounding the characters and the word meaning, but never asks the child how they interpret the story, it could cause a lot of problems surrounding reading development. It could also cause a child to become confused, fearful, even dislike reading altogether.

The missing piece of the puzzle is that no one asks the children how they feel about what they read or what they think about what they read. This no longer matters in the cold, mechanistic style of measurable educating, and, in this case, with reading instruction. We are hearkening back to the cold 1940s (close reading) schooling and calling it progress. Like everything else with Common Core, there are right answers and that’s it. There is no room for interpretation.

For example, the Federalist recently provided an interesting example of teachers learning about this new kind of reading instruction. Here they were learning to teach the Common Core English Language Arts (Here). The book the teachers were using to teach second grade summer school students, students who were having difficulty with reading already, was Eve Bunting’s Pop’s Bridge. Bunting is known for her gritty books, rich and provocative, like Smokey Night which deals with rioting, or Flyaway Home where a father and son live in an airport because they are homeless. Terrible Things is her book about the Holocaust with the message that people should not look away from wrongdoing.

Pop’s Bridge is a fictional account about two children whose San Franciscan fathers—one Asian and one Caucasian—helped build the Golden Gate Bridge. Robert, the white boy, believes his father has the most important job, he is a skywalker, building the bridge, and that his friend Charlie’s dad, a painter, has a job that is less important. But then both boys see workers die in a fall and Robert learns building a bridge involves “teamwork,” it is dangerous, and he loses his “superiority complex.”

First of all, is a book like Pop’s Bridge appropriate for kindergarten, even first or second grade? And wouldn’t a book like this need special handling if used with children, especially young children? I personally would not read this book to a kindergartner or first or second grader. And even in third grade it would depend on the children and their parents. I would handle a book like this with great care.

Scholastic considers this book appropriate for kindergarten. (Here).

With Pop’s Bridge, my guess is children, at the very least, would need to ask questions and have a very caring teacher describe the meaning of what happened in the story, especially involving the loss of life. I am equally stunned at how teacher’s, through Common Core, in the above mentioned article, are taught to drill children about the book.

In this instance, teachers do the asking of the questions. Students, who might have serious concerns of their own, who might wish to ask about the book, are pretty much ignored. They must answer what they are asked and if they miss an answer they are corrected.

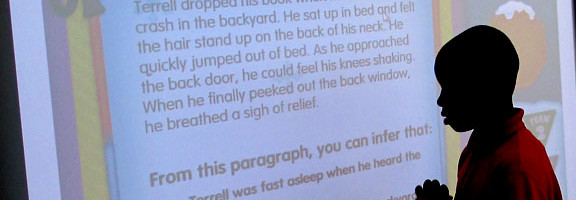

The teacher informs the student that they will ask “text-dependent questions,” (can you say text-dependent, Johnny?) which already seems cold, meaningless to a young child. Why use such words with children? In this case we are talking about seven-year-olds.

The students have books called Xeroxes where they must answer the right question. They are told to describe the important characters in the story and why they are important. When a child says that Charlie’s father is important, the teacher says “I like your text evidence.” Those words also sound dull and unappealing to teaching a child how to read. What’s wrong with, “good answer?”

When a child answers later that Robert is proud of his dad, she is asked how she knows, and her answer is because the “book says that.” The teacher must now backtrack to get the child to understand something more, so she goes over the fact that the father has an important job. When she later asks what does he keep calling the bridge, the child responds “the Golden Gate Bridge.” But that is incorrect. The right answer is “the impossible bridge.” Several of the children don’t seem to get this and are sent off to do extra work.

This kind of nuanced banter is truly risky business while teaching reading. Not only is it disruptive and trite, it also could leave children frightened about reading mistakes and, with this story, death. But no one seems to care because that is not what the teacher is directed to address.

I am not saying that Pop’s Bridge is a bad book, or that students might not benefit from discussing a book or its meaning. But I am, quite frankly, appalled that such a book is considered appropriate for kindergarten or first or second grade, and that teachers are using such a ridiculous format to teach reading. This is definitely an indication to me that whoever came up with this did not understand children and how they learn to read.

In other words, instead of text dependent, the words should be student-focused.

Thank you for questioning age appropriateness of literature. Kids are different, and a book like Pop’s Bridge can help the very sensitive child with excellent interpersonal and intrapersonal skills, to express ideas that would benefit children less mature in these areas. Teachers who are sensitive to differences can use a book like that wisely. It’s when kids are expected to have certain responses, or are graded on those responses, or are exposed to literature at length as a requirement (for example, reading a very depressing, disturbing novel in middle school and being asked to do multiple assignments on it and talk about it at length) that you run into some serious problems teachers and curriculum directors need to be aware of. I also think all teachers need to be sensitive to sensitive kids. They can be a real asset to a classroom, but don’t pressure them to engage in very emotional conversations.

Thank you, NP. I agree. Teachers need to know their students.

I agree that dealing with a story that involves death with a large group of young children could be difficult to navigate, but I’m confused about why you are associating this book or the practice of teaching “close reading” with the Common Core. When I read the standards, I don’t get any of this out of it. Is it because of the tests that will be connected to the standards? Are the children going to be asked for “text-dependent” details while being tested? That word/phrase never shows up in the Standards.

The use of close reading has been chosen by many as the best reading approach to use with Common Core State Standards. I think it is wrong to use it so strictly with young children. The example I chose was a good example of this. Thank you for your comment.

I believe it was the CCSS self-proclaimed architect, David Coleman who explained that no one cares what our children think once they are out in the real world. So he removed it from education since he was completely unqualified to even write anything in education.

That’s right, Meg. David Coleman never studied the needs of young children. He is not a teacher or a reading specialist. It is outrageous that he was given such broad authority to design what young children should learn. Thank you for commenting.

This is a great conversation to have. I personally like CC (or AL’s version of it) for high school. I’m always concerned about what my students think. For years I’ve said that if I could teach one thing, it would be to teach kids to think. To me it’s all about thinking deeply and being able to back up assertions. Of course we as teachers need to keep the teacherese to ourselves. “Text-based evidence” is probably a bad choice when speaking to first graders. Speak to students without the educational jargon.

I agree that the extended time with a novel, especially if its depressing, has its drawbacks. Again, the idea is to dig deep, so teachers are taking time to do just that.

I’m always interested to hear a good debate on educating the very young. I will sign off to find and read Pop’s Bridge.

I think the author here makes two well-meaning mistakes. She is using a piece of curriculum to judge the standards, and forgets that the standards are a floor, not a ceiling. The standards are clear that interpretation is at the center of a child’s encounter with a text.. I see nothing in the standards that constrains teachers or children in the ways described. I’m a high school teacher, and have a broad range of discussions with students about what they are reading. They are expected to come to the text with their own questions or connections. I would encourage teachers not to rely on curriculum guides or textbooks. Instead, they should be familiar with the standards. And then make choices about curriculum that are appropriate for their students.

Thanks for your comment, Steve. But I was talking about both standards and curriculum for very young children. Close reading has become associated with the standards…. I have yet to hear of teachers working towards the mastery of the standards letting children read the way they want to read. It is all measurable and dictated by the teacher. The fact that books for young children are even being aligned to standards is to me pervasive.

It is different in high school. Although I’m not crazy about Common Core State Standards in high school either. There is an overemphasis all around on nonfiction and informational text. And I question that the standards care that much about student expression. I happen to believe that student expression in narrative writing is one of the best things you can do for students in high school English classes contrary to what David Coleman, developer of the standards, has claimed.

I am not against some broad standards. Teachers have always had those. But that an elite group of non-educators devised these standards, which are totally unproven in their worth, is troublesome. To drive all class material and teaching towards mastery of these standards is equally troublesome.

I think it is important to show how the use of these standards is playing out in the classroom. That is what I attempted to do here.

Nancy, I suspect we teach in very similar ways, even though I pay close attention to alignment. This makes me think that the problem lies not with the standards but with curriculum, and the perception of standards by publishers. For instance, The role of informational texts in the ELA classroom is widely misunderstood. I hope that teachers will come to be responsible for their own curriculum and take an independent look at the standards for their grade level. I believe that the standards can accommodate all manner of styles and students.

Steve, As a blogger I appreciate this discussion.

I realize the CCSS supporters want everyone to think the standards are separate from the curriculum, but how can that be when you use words like alignment? How can teachers be independent when they are given these standards to begin with? They had no involvement in their creation!

Teachers will also gravitate towards what they are told will work. See my recent post. And many would argue that publishers worked hand-in-hand with the Core developers. I mean, name me a workbook today that doesn’t have the words Common Core in the title!