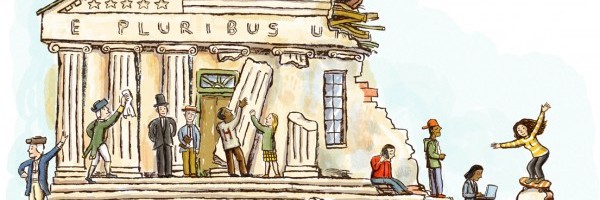

You are not just training our nation’s future workers. You are bringing up the future citizens of the United States of America. Your students will, someday soon, collectively decide the fate of this great nation of ours.

Supreme Court Justice, Sandra Day O’Connor (Supreme Civics, 2011)

I thought today would be a good day to discuss civics and the loss or reduction of its teaching in our public schools. We have always looked to public schools to teach students citizenship. But for years schools have done little to inform young people about their government and the meaning behind living in a democracy. Students learn little about local, state and federal governments. They don’t study much about the Constitution. If they’re lucky, they get some facts in a class that lasts a semester or a year. Many worry that young people are not learning to question.

Andrea Batista Schlesinger wrote The Death of “Why?: The Decline of Questioning and the Future of Democracy, where she discusses how the push in schools is for students to find answers, but they are not taught to think about what they are learning. “Our schools send the message to children that the answer is all that counts. We test children to death, conveying the idea that correctly filling in the bubbles is the same as learning.”

Civics today isn’t a robust class that stimulates questioning and debate. While high-stakes testing runs rampant through schools in reading and math, only 8 states, in 2012, bother to administer tests specifically in high school civics. California, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, Virginia and West Virginia have the honors. But even in those states, civics tests are standardized multiple choice questions and not thought provoking essays. There seems to be little interest in what students know in this area.

Public schools pay little attention to civics due to No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and Race to the Top (RTTT), although some may argue that they never really had a great civics class. This says to me that civics needs to be strengthened in public schools! But whatever civics students had in the past, any meaningful civics instruction was essentially destroyed by those two programs. When civics is spoken about now, it is more about how to test it.

In 2008, Sandra Day O’Connor stated that in the 1960s, “the typical U.S. Student was offered courses in government, democracy and civics.” But, she warned “formal civics has all but vanished from the curriculum in favor of courses that transmit a body of facts about the U.S. government and its history.”

Facts are good for multiple choice tests but what else?

In 2013, Congress introduced the Sandra Day O’Connor Civic Learning Act of 2013 which, among other things, awards competitive grants to nonprofit educational organizations to develop and implement programs that promote civic learning and engagement through instruction, professional development, and evaluations. HERE in full. I am not sure I understand why the focus should be on nonprofits and not direct engagement in our public schools. Why don’t more schools focus on civics classes? Why do we need nonprofits to do this job?

Sandra Day O’Connor herself started a nonprofit, iCivics, which is an online program with games sponsored by a whole list of corporations including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. While the program might have some merit, it is online. This surprised me because I thought Sandra Day O’Connor was working to get better civic programs into public schools—not going into the virtual ed. business. Although she justifies it by claiming that students are on computers so much, that she thought this was a way to reach them, and the program can be used in the classroom. I also spotted the words Next Generational somewhere on the website, which may be coincidental, but I am wondering if it has to do with Common Core.

Common Core has also been rolled out to be wonderful for civics. A group of individuals got together to discuss Common Core and civics at the Albert Shanker Institute (irony) and for the AFT (irony). HERE. I find it troubling that many of the same people who are indirectly, if not directly, responsible for getting rid of civics through NCLB and RTTT, are now clamoring to “reclaim the promise” and make the lost civics be a part of Common Core.

Earlier this year teacher Nicole Mirra in the Answer Sheet discussed how advocates of the Common Core think it will be good for civics, but while suggestions are made that it is important for democracy, it does “not help teachers or students actually make connections in any meaningful way.”

Mirra was responding to Ross Weiner’s article in the Atlantic called “The Common Core’s Unsung Benefit: It Teaches Kids to be Good Citizens.” The article claimed, the “Standards ‘identify’ the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution and Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.” But there is little to go on—to incorporate this into the curriculum.

Like the loss of geography, civics instruction under the Common Core, is sketchy. It is supposed to be built into the Common Core which specifies Reading/Language Arts. But, what’s needed, is a class purely dedicated to teaching civics and activities interspersed throughout elementary and middle school that have to do with civics in social studies. Unfortunately, many of the social studies classes are missing too!

Civics might be missing, but in some places youth organizing is occurring under the idea that young people should fix the problems of the country. I’m not sure if this is where the heavy push for high school students to do service projects occurred. Certainly, encouraging students to do service activities has value, but schools can go overboard. And students doing community organizing without learning about the meaning behind what they do, and the civics involved, seems a missing part of the equation. Students need to understand civics in order to facilitate lasting positive changes involving the causes they champion during high school and college.

Important on this day, however, is how many students grow up and vote. Do young people grow into adults that care about their government—how it works and their part in how the country is run? Do they see themselves as participants?

The Center For Information & Research On Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), from Tufts University, claims young people might not vote for the following reasons:

- Didn’t like the candidates.

- Not interested, felt my vote would not count.

- Too busy, conflicting work.

- Registration problems

- Out of town or away from home.

Needless to say, some of the rest of us might feel the same as the students. But for young people, you make your priorities often with what you have been taught is important. Isn’t it time to bring back real civics education to our public schools–

References

Supreme Civics. Principal Leadership. October 2011. 1-5.

Schlesinger, Andrea Batista. The Death of “Why?: The Decline of Questioning and the Future of Democracy (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koeler Publishers, Inc., 2009), 3.

Leave a Reply